Chesterton on the sanity of commitment

Let’s be honest, commitment isn’t really a Western strong suit. We’re all about freedom: being untethered, unrestricted, unlimited and un-beholden.

Commitment seems like the antithesis of this philosophy. It binds, restricts, restrains and commands. So why make commitments at all?

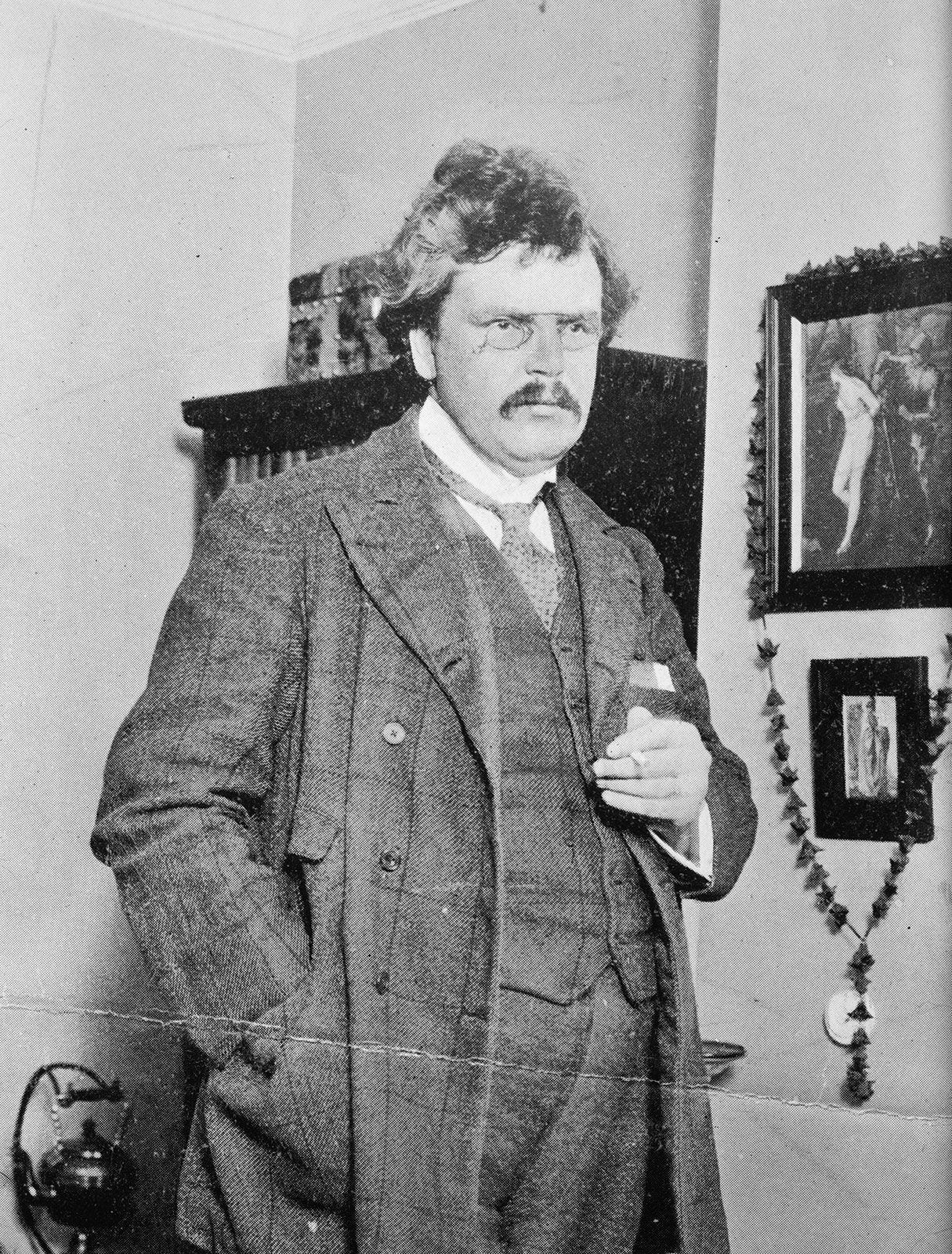

According to the late British writer and philosopher G.K. Chesterton, much of the Western aversion to commitment stems from misconceptions, fears, and insecurities. His essay A Defense of Rash Vows claims that one ought to make commitments because they are, in actuality, the only true path to freedom.

But before we can effectively talk about this freedom, we must first discuss some common causes of commitment-aversion.

I. Fears of Inadequacy

According to Chesterton, fear of commitment may be driven less by opportunism (wanting to keep one’s options open) and more by a deep-seated sense of inadequacy. He writes:

A man who makes a vow makes an appointment with himself at some distant time or place. The danger of it is that himself should not keep the appointment. And in modern times this terror of one’s self, of the weakness and mutability of one’s self, has perilously increased, and is the real basis of objection to vows of any kind.

He saw that many people fear they aren’t consistent enough to reach the end of a commitment. They are deeply aware of how malleable they are, lacking faith that they can finish what they start. They fear that perhaps they will be “another man” before their commitment is over.

But these fears seem to share a common misconception: that commitments are fixed, static and require perfect execution.

This is, of course, false.

Commitments don’t halt our growth—they facilitate it.

They don’t require perfection, but actually uniquely reveal our inadequacy. This isn’t a reason to avoid commitment, but to run to it.

We may be “another man” by the end of our commitments, but that’s actually the goal.

II. The painless pleasure fallacy

According to Chesterton, the second variable driving aversion to commitment is peoples’ illogical desire for pleasure without any cost. We all know someone who’s ventured into the murky waters of pleasure with “no strings attached.”

Perhaps it always seems to end in disaster because it’s an “insane attempt to obtain pleasure without paying for it.”

Chesterton first introduces this point by commenting on those who oppose the institution of marriage.

They have invented a phrase, a phrase that is black and white contradiction in two words - ‘free-love’- as if a love ever had been, or ever could be, free. It is the nature of love to bind itself, and the institution of marriage merely paid the average man the compliment of taking him at his word.

He then extends the scope of this phenomenon to explain how across multiple domains, people want to extrapolate pleasure from pain.

Everywhere there is the persistent and insane attempt to obtain pleasure without paying for it. Thus, in politics the modern Jingoes practically say, ‘Let us have the pleasures of conquerors without the pains of soldiers: let us sit on sofas and be a hardy race.’ Thus, in religion and morals, the decadent mystics say: ‘Let us have the fragrance of sacred purity without the sorrows of self-restraint; let us sing hymns alternately to the Virgin and Priapus.’ Thus in love the free-lovers say: ‘Let us have the splendor of offering ourselves without the peril of committing ourselves.;

Chesterton offers commitment as a resolution to the paradoxical insanity of longing for pleasure without any strings attached. He argues that in a fallen world where pleasure, meaning and suffering are inextricably linked, commitment serves as the binding agent.

There are thrilling moments, doubtless, for the spectator; the amateur and the aesthete; but there is one thrill that is known only to the soldier who fights for his own flag, to the ascetic who starves himself for his own illumination, to the lover who makes finally his own choice. And it is this transfiguring self-discipline that makes the vow a truly sane thing.

III. The Freedom of Commitment

Ultimately, Chesterton sets up a complex explanation for how commitment is in actuality, the only true path to freedom. He helps us to see this by dissecting the nature of freedom, not strictly as boundless potentials and absence of coercion, but as an actual ability to act.

He understood that all action fundamentally requires commitment, because it begins at the level of choice. Some choices which lead to action are conscious, others unconscious, but all require some level of commitment.

The Bottom Line

You might fail to keep your commitments. Or, the circumstances in which said commitments are made could become void naturally, despite your desire to keep them. The point is not to beat yourself over the head for the commitments that you’ve failed to keep, in your fallible human state. There is grace.

Rather, it’s to get to a place of doing two things: become wise in making commitments that are meaningful and worthy of your time, and then embrace said-commitments without fear. You won’t be enough, and that is why there is grace.